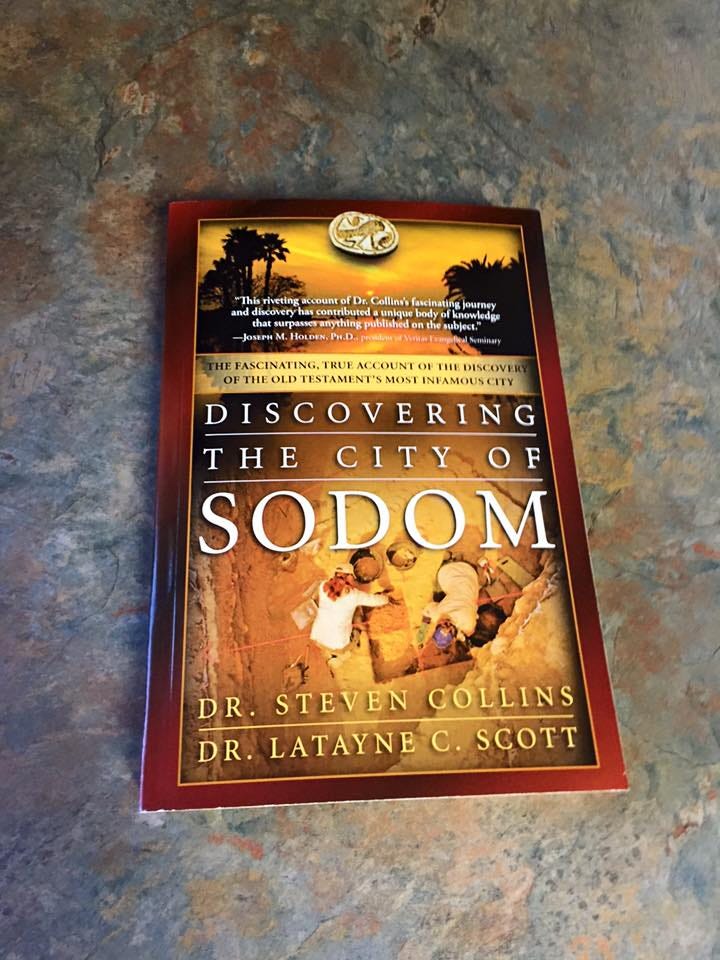

Discovering the City of Sodom: The Fascinating, True Account of the Discovery of the Old Testament's Most Infamous City

by Dr. Steven Collins and Dr. Latayne C. Scott, Howard Books/Simon & Schuster, 2012

I’d like to begin posting first chapters of my books (published and in progress) on Wednesdays.

What follows is not the beginning of this co-authored book, Discovering the City of Sodom, but it’s my favorite passage. Why? Because, for one of the few times in my life, I was able to exactly describe what I saw, there in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Here is a link to the book.

Who is the ideal reader for this book? If you’re looking for support for the veracity of the Bible, if you like ancient history and treasure hunts, and if you want to read about a true hero of the faith, this is the book for you — or for someone with those same interests. Take a look at the online reviews, and consider giving the book as a gift to someone or to yourself!

Jordan, the Home of the Biblical Site of Sodom

A map of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, the home of Sodom, reveals it to be a bedfellow to Israel, backing the spine of its entire western border up to the Jordan River that gives it its name. On a map, its roads are knotted veins and arteries around its central city, Amman. Eventually the clot loosens and sparse highways meander west, or drip down to the tourist spots on the shore of the Dead Sea where dates grow with water ten times saltier than other plants can stand, and every other living thing drinks purified water or lives in soil repeatedly washed to leach out the minerals.

Then, on either side of those massive life-numbing waters, are the places and sights that contrast with Sodom, that by the descriptive friction between them define Sodom. What the Dead Sea is, Sodom is not. What the desert is, Sodom is not. And yet they were part of both the backstory and the aftermath of what happened to Sodom, in the record of a kingdom left behind in the buildings and artifacts they used.

Every visitor should come to the Dead Sea at night the first time. Going down into the valley of deadness, every driver tap, tap, taps his brakes. A persimmon-colored moon looks like a cupped hand to the sky, asking for rain. Across the water, the lights of Israel flicker.

Water bottles cringe and collapse. Everything inclines toward and yields to the loss of altitude. In the distance, the hotels are outposts of green and florescence along the shore of the great silver lake.

In daylight there is more to see, but away from the water, everything is dusted in sand. The most famous ancient site in southern Jordan, indeed in all of Jordan, is Petra. Unfortunately the Bible omits notice of it and the name of its builders the Nabateans. That rosy-pink city lay long hidden in a cleft of rock and forgotten for millennia, but now attracts everyone from movie producers to hundreds of thousands of tourists a year who have their breath taken away by its unexpected beauty. For many, Petra defines the ancient world of Jordan.

Other than those rose-colored facades and the few modern cities, everything in Jordan comes off three color palettes. There’s the green-green of banana fields and dusky-green of the country’s twelve million olive trees; there’s earth in all its variations of one sand-shade to another; and there’s the wild micro-palette of human occupation, with houses painted colors from glaring white to Pepto-Bismol pink, with trucks sporting psychedelic murals on their cargo panels, with intricately-patterned rugs slung over roofs and porch walls and secured against the searing wind’s power by plastic lawn chairs whose legs span exactly the distance to act as giant clothespins.

Though many of the homes are luxurious inside, what a westerner would regard as their yards are concessions of defeat to the enemies of grit and wind. Black plastic garbage bags and little white shopping bags balloon in the breezes and hang in thorny tree branches. And almost every home in the countryside looks like an insect bristling with multiple antennae of rebar from its roof.

Jordanians call the rebar a sign of hope: Everyone builds a bottom story and then says, “I hope I get an inheritance, I hope my daughter marries a rich man, I hope my business deal goes through so I can build a second story on this house.”

Traveling on one of the oldest highways in the world still in use, the King’s Highway that runs from Aqaba to Damascus via Amman, is an adventure even on the paved main roads that follow its route in the twenty-first century. Somewhere between Petra and the Dead Sea is where Moses asked the Edomites if he could pass through with his horde of exiles, and the Edomites’ refusal ostensibly cost the Israelites a great deal of distance and trouble (Numbers 20:14-21.)

Or maybe not. Shortcuts in Jordan take exactly the same amount of time as the long way. Jordanian guides often concur when they can’t get their tour bus microphone switches to work, and then remember to speak with the “on” button in the “down” position: “Everything is backwards in Jordan.”

The small towns all look alike, with the ubiquitous Muslim versions of the neighborhood bar that serves thick black coffee. On nearly every corner are the aluminum cases outside shop doors that contain rotisseries of what Tall el-Hammam excavation crews call GSC—“greasy spinning chickens.”

Anywhere near the highway is a dangerous place for pedestrians who are fair game for any motorized vehicle, and people hurry across with wide eyes and robes streaming out behind them. A Mercedes-Benz bus just barely misses a truck with a hand-painted tailgate that reads “NI55AN” and careens from side to side in what is nervously referred to as “surfing Jordan.”

The Muslim call to prayer wafts out over the sound of honking horns, shouting vendors, and the near-shouts of “normal” Jordanian discourse. Here, the mosques and minarets range from the colorless and austere, to some of which have strings of blinking neon lights not unlike those on the coffee shops.

Yet there are areas with high percentages of Christian believers, too, such as Madaba, where one in five of its residents is a Christian. It even has a mosque named “Jesus the Son of Mary.”

In Madaba is a rare, non-ancient attraction: the St. George Greek Orthodox church whose 1500-year old mosaic floor was discovered during a restoration in 1884 BCE. There in the tiles is the oldest map of the Holy Land in existence, even showing still-identifiable features of Jerusalem and other sites.

Most exciting of all for those who seek Sodom and Gomorrah in the details of that tiled depiction are two mosaic “cities” right where the Bible says they should be—in the Kikkar of the Jordan; though, unfortunately the writing on the Madaba Map identifying them has been lost.

Compared to Israel, Jordan has many fewer biblical sites and the distances between them is great, but that’s because the nation of Israel went west across the Jordan under Joshua’s command and for the most part from that time forward lived on the other side of the river.

Mount Nebo, where God showed Moses a panoramic view of the Holy Land (Deuteronomy 34:1-3), is all caliche and rough rocks, accessible via a stomach-coiling ride up a sand-scrubbed and lurching road. Even more remote is the seeming road to nowhere that ends at the edge of the Arnon Gorge where the ruins of Aroer (Deuteronomy 2:36) teeter on the edge of the remote bottom of the precipice.

The site of Dibon is remarkably unassuming given the spectacular nature of a basalt slab found there. On it, an inscription that was broken into pieces in modern times to increase its marketability was nonetheless reassembled and includes the name of King Omri, confirming the narrative of 2 Kings 3:4-5 in the Bible.

Then there is Makawer (Machaerus), the site where John the Baptist was incarcerated (Matthew 14:3) until his head was sent by courier to Herod Antipas’s wife Herodias at a party going on the palace upstairs. His captors had dragged this man, his bones made of insect shells and whose veins ran half honey, along these skidding stones and slammed him into one of the many caves that dot the slopes of the hill below the fortified compound. Though Roman walls still stand atop the prominence, these caves are history without the ruins, an enclosure of emptiness that says more than edifice.

These are desolate desert places where even broad-leafed cacti slump and shrivel. Goats quick-step from shade to shade, even in the winter. Water is so precious here that Jordan’s pipelines bear bullet holes where Bedouins, who camp in sprawling grey tents with plasma televisions inside, make their own impromptu utility connections to water their flocks.

To come back up the eastern side of the Great Salt Sea from its southern end along the cliffs is to be sandwiched between two deaths. On one side are the rugged sandstone cliffs whose very curves grasp and rasp the eyes. On the other side is a lifeless body of water. Travelers in this area from the beginning of time go north, because there is only more bleak death to the east.

Just as everyone goes up to Jerusalem, so everyone goes up when moving away from the lowest spot on earth, the Dead Sea. The Kikkar of the Jordan, the breadbasket of the Jordan Valley, lies just north of the Dead Sea. Here the Jordan River has overflowed its banks annually and the alluvial soils for millennia have washed down from the mountains, forming in antiquity some of the most fertile soil in the region.

This is the place that Moses described as a “well-watered, like the garden of Yahweh, like Egypt” (Genesis 13:10).